In the first post,

If We Want To vs. If We Can, we examined two ways of viewing human behavior in relation to success. One is based on motivation – “people do well if they want to” and one is based on having the necessary abilities and resources – “people do well if they can.” Now, we’ll consider the perspectives of those who’ve experienced trauma within that context, and why this can complicate relationships.

For our purposes, let’s imagine a person who believes, for whatever reason, that if they truly wanted to do well, they would. Their success is reliant on motivation, which means that their own sense of self-worth is linked to the outcome. If they are successful, this belief is validated, and the cycle continues. If they are unsuccessful, as we all can be, they take it hard. They don’t realize that failing at a particular task doesn’t make them a failure. In these cases, and especially for those who are or have experienced trauma, the cycle illustrated here can occur.

The belief that “If I really wanted to do something, I would be able to” can result in a lowered sense of efficacy and self-esteem. They may feel that their ability to produce a certain result is diminished, which can lead to the opinion, “I am not able” or they may lose confidence in their own self-worth, which can lead to the opinion, “I am not good.” Naturally, these feelings can lead to additional avoidance, anger, and apathy, at which point they’re likely to give up on the task, and worse yet, on themselves.

This is a cycle in which one incorrect belief feeds into the next and can only be interrupted by rational thought such as, “There’s an ability or resource I’m missing to make this happen” or “I can learn something from this attempt that will allow me to access what I need to do better next time.” The problem is that this requires previous experience to act as proof that, despite a failed attempt, we can eventually succeed. But trauma’s effects can distort or interrupt this rationale. This is particularly true for children, whose brains are still developing.

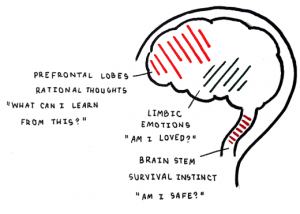

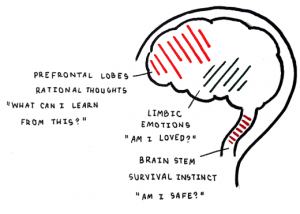

Illustrated here, the three parts of the brain most important in understanding how trauma is internalized are the prefrontal lobes, the limbic system, and the brain stem.

· The prefrontal lobes are responsible for receiving information from our senses, which is used to form rational thoughts, or those established by experience. It asks and answers, “What can I learn from this?”

· The limbic system is responsible for registering and responding to our emotions. It also assists in the formation new memories about our experiences. It asks and answers, “Am I loved?”

· The brain stem is responsible for monitoring our internal functions, like heart rate and breath, and our survival instinct. It asks and answers, “Am I safe?”

Adults, whose brains are developed in relatively safe environments or have found ways to be resilient to the challenges they have faced, are able to make complex, well-informed decisions. However, children, whose brains are undeveloped, aren’t. To ensure their survival, infant brain’s stress response is stuck on “on,” and it’s only through experiences throughout childhood that it will learn to adapt to new conditions on a case-by-case basis. Because young children aren’t able to weigh costs and benefits, their rational thought processes take a backseat to their natural instincts. This is especially true for children who’ve experienced trauma, where the negative effects of trauma leaves the brain much less able to decipher what is safe and what is not.

This is of critical concern for many reasons, one of which is the long-term effects of trauma. If left untreated, a child who experiences trauma will likely have behavioral, cognitive, and/or emotional setbacks which can extend into adolescence and adulthood. Their symptoms may manifest into a basic mistrust of adults, a belief that the world is an unsafe place, a belief that bad things will happen and it’s their fault, the assumption that others will not like them, fear and pessimism about the future, and a sense of hopelessness and lack of control. Any of these may impair the ability to make well-informed decisions, which can, in turn, lead to poverty, dysfunction, and/or systems engagements. If they have children, they can then become impaired caregivers, and might lack the abilities and supports to raise their children free from the impact of trauma.

Often, the effects of trauma show up in behavior too. Children may be sensitive to noise, avoid touch, have heightened reflexes, demand lots of attention, be perfectionistic, be aggressive, be confused about what is dangerous, or resist separations from familiar people or places, just to name a few.

It’s incredibly important to remember that this cycle can be interrupted at any point, which is where you fulfill your role as a caregiver. Yours is rewarding and valuable work, but it isn’t easy. You are faced with the hardship and pain of others, so it’s understandable that you might struggle after encountering children with complex challenges. As mentioned previously in

If We Want To vs. If We Can, this is called compassion fatigue, and we’ll examine what compassion fatigue is, how it works, and some solutions to help build compassion resilience in our next post. Be sure to check back next month for our latest post, sign up for the WISE newsletter, attend a WISE meeting to get more involved, or visit our website by clicking

here.

Thanks,

Lucy, and the WISE team

For our purposes, let’s imagine a person who believes, for whatever reason, that if they truly wanted to do well, they would. Their success is reliant on motivation, which means that their own sense of self-worth is linked to the outcome. If they are successful, this belief is validated, and the cycle continues. If they are unsuccessful, as we all can be, they take it hard. They don’t realize that failing at a particular task doesn’t make them a failure. In these cases, and especially for those who are or have experienced trauma, the cycle illustrated here can occur.

The belief that “If I really wanted to do something, I would be able to” can result in a lowered sense of efficacy and self-esteem. They may feel that their ability to produce a certain result is diminished, which can lead to the opinion, “I am not able” or they may lose confidence in their own self-worth, which can lead to the opinion, “I am not good.” Naturally, these feelings can lead to additional avoidance, anger, and apathy, at which point they’re likely to give up on the task, and worse yet, on themselves.

This is a cycle in which one incorrect belief feeds into the next and can only be interrupted by rational thought such as, “There’s an ability or resource I’m missing to make this happen” or “I can learn something from this attempt that will allow me to access what I need to do better next time.” The problem is that this requires previous experience to act as proof that, despite a failed attempt, we can eventually succeed. But trauma’s effects can distort or interrupt this rationale. This is particularly true for children, whose brains are still developing.

Illustrated here, the three parts of the brain most important in understanding how trauma is internalized are the prefrontal lobes, the limbic system, and the brain stem.

For our purposes, let’s imagine a person who believes, for whatever reason, that if they truly wanted to do well, they would. Their success is reliant on motivation, which means that their own sense of self-worth is linked to the outcome. If they are successful, this belief is validated, and the cycle continues. If they are unsuccessful, as we all can be, they take it hard. They don’t realize that failing at a particular task doesn’t make them a failure. In these cases, and especially for those who are or have experienced trauma, the cycle illustrated here can occur.

The belief that “If I really wanted to do something, I would be able to” can result in a lowered sense of efficacy and self-esteem. They may feel that their ability to produce a certain result is diminished, which can lead to the opinion, “I am not able” or they may lose confidence in their own self-worth, which can lead to the opinion, “I am not good.” Naturally, these feelings can lead to additional avoidance, anger, and apathy, at which point they’re likely to give up on the task, and worse yet, on themselves.

This is a cycle in which one incorrect belief feeds into the next and can only be interrupted by rational thought such as, “There’s an ability or resource I’m missing to make this happen” or “I can learn something from this attempt that will allow me to access what I need to do better next time.” The problem is that this requires previous experience to act as proof that, despite a failed attempt, we can eventually succeed. But trauma’s effects can distort or interrupt this rationale. This is particularly true for children, whose brains are still developing.

Illustrated here, the three parts of the brain most important in understanding how trauma is internalized are the prefrontal lobes, the limbic system, and the brain stem.

· The prefrontal lobes are responsible for receiving information from our senses, which is used to form rational thoughts, or those established by experience. It asks and answers, “What can I learn from this?”

· The limbic system is responsible for registering and responding to our emotions. It also assists in the formation new memories about our experiences. It asks and answers, “Am I loved?”

· The brain stem is responsible for monitoring our internal functions, like heart rate and breath, and our survival instinct. It asks and answers, “Am I safe?”

Adults, whose brains are developed in relatively safe environments or have found ways to be resilient to the challenges they have faced, are able to make complex, well-informed decisions. However, children, whose brains are undeveloped, aren’t. To ensure their survival, infant brain’s stress response is stuck on “on,” and it’s only through experiences throughout childhood that it will learn to adapt to new conditions on a case-by-case basis. Because young children aren’t able to weigh costs and benefits, their rational thought processes take a backseat to their natural instincts. This is especially true for children who’ve experienced trauma, where the negative effects of trauma leaves the brain much less able to decipher what is safe and what is not.

This is of critical concern for many reasons, one of which is the long-term effects of trauma. If left untreated, a child who experiences trauma will likely have behavioral, cognitive, and/or emotional setbacks which can extend into adolescence and adulthood. Their symptoms may manifest into a basic mistrust of adults, a belief that the world is an unsafe place, a belief that bad things will happen and it’s their fault, the assumption that others will not like them, fear and pessimism about the future, and a sense of hopelessness and lack of control. Any of these may impair the ability to make well-informed decisions, which can, in turn, lead to poverty, dysfunction, and/or systems engagements. If they have children, they can then become impaired caregivers, and might lack the abilities and supports to raise their children free from the impact of trauma.

Often, the effects of trauma show up in behavior too. Children may be sensitive to noise, avoid touch, have heightened reflexes, demand lots of attention, be perfectionistic, be aggressive, be confused about what is dangerous, or resist separations from familiar people or places, just to name a few.

It’s incredibly important to remember that this cycle can be interrupted at any point, which is where you fulfill your role as a caregiver. Yours is rewarding and valuable work, but it isn’t easy. You are faced with the hardship and pain of others, so it’s understandable that you might struggle after encountering children with complex challenges. As mentioned previously in If We Want To vs. If We Can, this is called compassion fatigue, and we’ll examine what compassion fatigue is, how it works, and some solutions to help build compassion resilience in our next post. Be sure to check back next month for our latest post, sign up for the WISE newsletter, attend a WISE meeting to get more involved, or visit our website by clicking here.

Thanks,

Lucy, and the WISE team

· The prefrontal lobes are responsible for receiving information from our senses, which is used to form rational thoughts, or those established by experience. It asks and answers, “What can I learn from this?”

· The limbic system is responsible for registering and responding to our emotions. It also assists in the formation new memories about our experiences. It asks and answers, “Am I loved?”

· The brain stem is responsible for monitoring our internal functions, like heart rate and breath, and our survival instinct. It asks and answers, “Am I safe?”

Adults, whose brains are developed in relatively safe environments or have found ways to be resilient to the challenges they have faced, are able to make complex, well-informed decisions. However, children, whose brains are undeveloped, aren’t. To ensure their survival, infant brain’s stress response is stuck on “on,” and it’s only through experiences throughout childhood that it will learn to adapt to new conditions on a case-by-case basis. Because young children aren’t able to weigh costs and benefits, their rational thought processes take a backseat to their natural instincts. This is especially true for children who’ve experienced trauma, where the negative effects of trauma leaves the brain much less able to decipher what is safe and what is not.

This is of critical concern for many reasons, one of which is the long-term effects of trauma. If left untreated, a child who experiences trauma will likely have behavioral, cognitive, and/or emotional setbacks which can extend into adolescence and adulthood. Their symptoms may manifest into a basic mistrust of adults, a belief that the world is an unsafe place, a belief that bad things will happen and it’s their fault, the assumption that others will not like them, fear and pessimism about the future, and a sense of hopelessness and lack of control. Any of these may impair the ability to make well-informed decisions, which can, in turn, lead to poverty, dysfunction, and/or systems engagements. If they have children, they can then become impaired caregivers, and might lack the abilities and supports to raise their children free from the impact of trauma.

Often, the effects of trauma show up in behavior too. Children may be sensitive to noise, avoid touch, have heightened reflexes, demand lots of attention, be perfectionistic, be aggressive, be confused about what is dangerous, or resist separations from familiar people or places, just to name a few.

It’s incredibly important to remember that this cycle can be interrupted at any point, which is where you fulfill your role as a caregiver. Yours is rewarding and valuable work, but it isn’t easy. You are faced with the hardship and pain of others, so it’s understandable that you might struggle after encountering children with complex challenges. As mentioned previously in If We Want To vs. If We Can, this is called compassion fatigue, and we’ll examine what compassion fatigue is, how it works, and some solutions to help build compassion resilience in our next post. Be sure to check back next month for our latest post, sign up for the WISE newsletter, attend a WISE meeting to get more involved, or visit our website by clicking here.

Thanks,

Lucy, and the WISE team